Diving into Nose Dive(s)

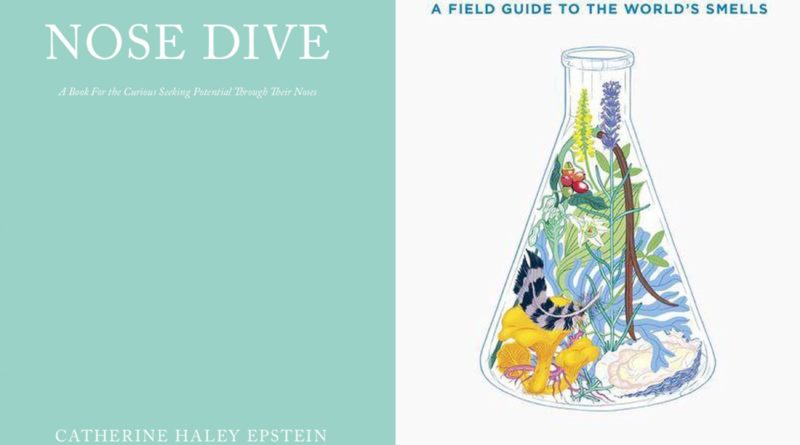

This year of anosmia and urban scent transitions due to Covid-19, saw the appearance of a remarkable number of books on scent. And not one, but two of them carry the enticing title “Nose Dive”. One is written by the widely acclaimed culinary expert Harold McGee, and the other by the renowned artist and olfactory art critic Catherine Haley Epstein. They couldn’t complement each other better when it comes to content and perspective: while McGee’s ‘field guide’ is written from a material point of view, Epstein’s book starts from human experience. Here you can read the reviews by scent historian Caro Verbeek

Nose Dive by Harold McGee – the Genesis of Scents

McGee’s book makes a huge impression even before turning one page, because it literally is just that. It is heavy, thick and sturdy, almost like a Bible. After opening it, the thin and numerous pages add to this association. And just like in the ancient textbook one can browse it, pausing at stories that grab our attention or speak to us, skip other parts, and endlessly go back and forth.

The author takes on a chemical perspective on almost every thinkable scent on the planet: trees, flowers, water, soil, mosses, weeds, fruits, human beings, animals and so on and so on. Particularly intriguing is his incredibly detailed table of animal excretions, from which we can learn that bird shit consists of ‘metabolizing uric acid’ that emit ‘ammonia and amines’ in the process, whereas the typical scent of horse dung comes from ‘microbes metabolizing proteins’ that give of smelly (or fragrant) ‘cresols, phenols and indoles’. Who knew? And what does this actually tell us?

Well, it mostly says something about the microcosm behind scents, such as microbes, molecules and larger compounds, and how they are responsible for the world of smell. Of course, human olfactory experience starts to make sense in the light of religious and socio-economic context, but that’s not the angle here. Yet McGee occasionally takes us on historical trips, explaining how tree resins were used as burnt offerings for example.

The major classification McGee entertains is ‘given’ as opposed to ‘chosen’ scents, the latter one subdivided into fragrance and food (cooked and fermented). The cultural phenomenon of burning resins such as myrrh and frankincense to communicate to divine beings can be captured by fragrance, and food speaks for itself of course.

Terpy, dirty and gaiachor: olfactory language speaks to the mind and the heart

The language the food expert uses to describe scents is very similar to that of chemists and perfumers and mostly accessible to laymen: fruity, floral, herbaceous, earthy are just some of the examples, as is ‘terpy’ (referring to ‘terpenes’) which is used for pine tree resins. He also uses more ‘hedonic’ words such as ‘dirty’ when it comes to ‘indolic’ (excrement like) jasmine. Something we can better understand when we realize it contains ‘indole’: an odorant that is present in many white flowers, but also in human excrements. ‘Fecal’ is another appropriate descriptor for that.

McGee even invented an entirely new word to catch that typical odour emanating from the earth after a rain storm: ‘gaiachor’. This word could replace the universally appreciated ‘petrichor’ (which means fragrant fluid running through the veins of the gods [ichor in Greek] that originates from stones [petra in greek]), he argues, because it is emitted by the earth.

My favourite newly acquired word however is ‘furfural’, which McGee defines as “sweet-smelling, tobacco like which is generated by fungi as they break down cellulose of autumn leaves”. It makes me want to cuddle a forest floor right now.

Nose Dive by Catherine Haley Epstein – Putting Your Nose to Work

Physically lighter and thinner, but ever so elegant and comprehensive is Epstein’s book on olfactory art and philosophy. If McGee’s book is all about chemistry, Epstein’s book is all about the meaning we attribute to scent. It is designed to activate the reader and stimulate both conscious smelling, and critical thinking about olfaction from a cultural perspective (which McGee might classify as ‘chosen’). It contains accessible articles on the history of olfactory art or scent making (not just perfume!), olfactory language and science.

Activating the nostrils

What makes “Nose Dive” so compelling are the exercises. In fact, the title of the book refers to user engagement: “To “dive right in” is to have agency, and it’s active. It implies being playful, and uninhibited, but with consequence”, the author explains. Epstein: “Scent – besides being material – is all about experience, so I created this diving board that invites readers to research their own olfactory environment”.

One of the exercises is quite challenging: “describe the smell of masking tape”. “Your brain trying to solve that puzzle is a unique creative act. And while we might not come up with the “perfect” description of said tape, we will have given our brain a welcome respite of hanging out in an abstract space”, she said. Another exercise that really gets your creative mind going is “Imagine you are making a capsule to send to aliens. Create a list of top ten smells of planet earth, in order to prepare them for a visit.” I immediately started thinking about petrichor (‘gaiachor’?), but also body odours, that we so actively try to get rid of. What if aliens only engage in chemical communication?

Talk to the Nose

Epstein – with whom I had the pleasure of working together on the ‘odorbet’ (a growing collection of smell related words, https://www.odorbet.com/) – included a chapter on olfactory language and smell descriptors, which she emphasizes are often based on sources and materiality and, within perfumery, commercially informed. ‘Fragrance wheels’ are often divided into ‘floral’, ‘woody’, ‘fruity’, ‘chypre’ or ‘oriental’ perfume families. The latter is a western invention that doesn’t do justice to non-western olfactory practices, she argues.

Epstein included a list with playful words such as ‘creepy amber’, ‘nasal persuasion’ and ‘period nose’. This concept is very useful for historians that want to demonstrate that the experience of smell is culturally, and therefore also historically determined, rather than just physiologically.

Complementary angles

Diving into the world of smells nose first can be truly adventurous. Both books ooze the scent of rigid dedication and enthusiasm. And while they couldn’t be more different when it comes to content and perspective, both display a vast knowledge and fascination for our most enigmatic sense. The books also demonstrate how talking about smell and critically thinking about olfactory phenomena, requires a very specific language. And both succeed in offering tools to enrich our very poor vocabulary.

Pingback: The Olfactory Report 1: Smellicopters and the Smell of Old Books * Catherine Haley Epstein - Aromatica Poetica